Strategic Insights in China: a Market Landscape Overview

While the forecasted 2025 GDP growth is now around a historical low of 3.8%, down from 5% in 2024 (source: IHS Markit), China has been building, for more than 20 years, an international business, geopolitical, and technological landscape that can allow the country to face major turmoil.

A long-term envisioned business journey

A manufacturing expert and an export champion for several decades, China has gradually shifted its position on the international stage to become a key global player — so much so that referring to China as an emerging economy sounds like an oddity nowadays. It has managed this transition in less than 50 years since its opening in the late 1970s. The real breakthrough came with its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, while its externalisation strategy — aimed at exporting and outsourcing its activities and developing its global building potential — was initiated in the 1990s.

Since joining the WTO, China has significantly modernised its political and economic framework to transform its “world’s factory” economic model into that of a global player, now capable of directly and successfully competing abroad in almost all sectors and territories.

To do so, China gradually deregulated its outgoing foreign direct investment (FDI) legislation, heavily subsidised the rationalisation of its State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), closed non-profitable “zombie” plants, and vertically integrated the full supply chain to rationalise costs and structures.

The Chinese government has strongly encouraged its network of public and private companies to roll out investments abroad — stimulating global demand with cheaper bids, opening new export markets, acquiring and building strategic assets to secure access and innovation in technology, energy, and mineral resources.

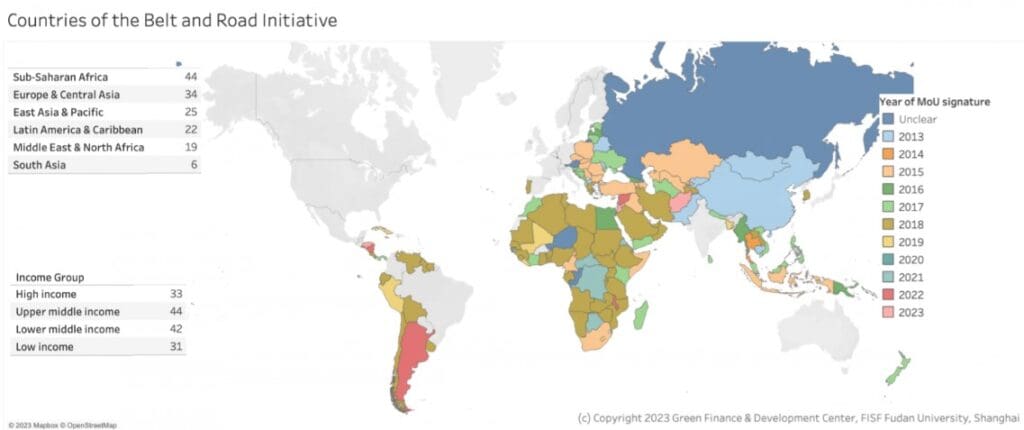

To complete the move, China released in 2013 a key programme among others, called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the new and enhanced version of the ancient Silk Roads — the famous trade routes linking Chinese merchants to the Mediterranean basin since antiquity. The BRI was and still is a game changer, especially among non-OECD countries. China started to allocate loans, invest, and construct infrastructure around the world.

On one hand, the BRI and other FDI programmes led by public and private interests have built from scratch or renewed multiple trading routes, equipping them with heavy industries, energy plants, ports, and bridges — facilitating daily life and raising new business opportunities for themselves, the countries of implementation, and third players by developing a level playing field and visibility in countries often neglected by key global players.

They have, on the other hand, among other issues, externalised the negative effects of some heavy industries by financing and operating entire ecosystems abroad, such as the Tsingshan Sulawesi Industrial Park, to name just one — but one that represented an unpredictable milestone for the stainless steel world, adding instability to the already unfair and unbalanced conditions of the sector.

Nonetheless, at a macro level, this Belt Road program of infrastructural investments gave China the opportunity to become a true player in global trade. By adding to its portfolio more than 150 countries involved in the Initiative or similar unlabelled projects, China has ensured, for itself and for others, access to new markets, new resources, new suppliers, and new customers.

The country is furthermore neighbouring a lot. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), signed in 2020 between Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and the ten countries of ASEAN — totalling around 30% of both the world population and global GDP — has the foundations to gradually eliminate customs duties on over 90% of goods. No doubt it will enhance regional trade, as was the case within the European Union.

Together with other international business and political approaches such as:

- the BRICS (Trade partnership of 2009 between Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, recently joined in 2024 by Egypt, UAE, Ethiopia, and Iran, then Indonesia joining in 2025),

- the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), implemented in 2013, welcoming as members or observers Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Cambodia, India and Pakistan, Iran, Mongolia, Nepal, Russia, Sri Lanka, and Turkey,

- the ongoing discussion with the EU to permanently solve unbalanced and subsidised capacities and other issues such as the WTO mutual obligations and responsibilities,

- the bilateral talks with all countries — with the Middle East, Africa, Central Asia, and the Americas.

China enrooted its blueprint and developed strong business and diplomatic ties year after year, project after project, taking the opportunity when accurate and available.

The outcome is that China now has a net global footprint and a pool of key partners in and outside its historical OECD business ties. The breadth of its portfolio logically strengthens the country’s ability to offset some losses by rerouting towards other markets.

The Climate Issue and Economy Is Embedded

Another path for growth is the intimate knowledge China has about the climate. Anyone who visited Beijing in 2015 remembers the thick polluting fog covering the north of the country. From 2018, China released the Blue Sky Plan. The government attempted to consolidate industrial overcapacities — with ambiguous success — by externalising some of its industrial negative impact as seen above. However, it deepened pollution control obligations and efficiency improvements across all end-use sectors (industry, appliances, buildings). The state of pollution in Beijing has greatly improved since then.

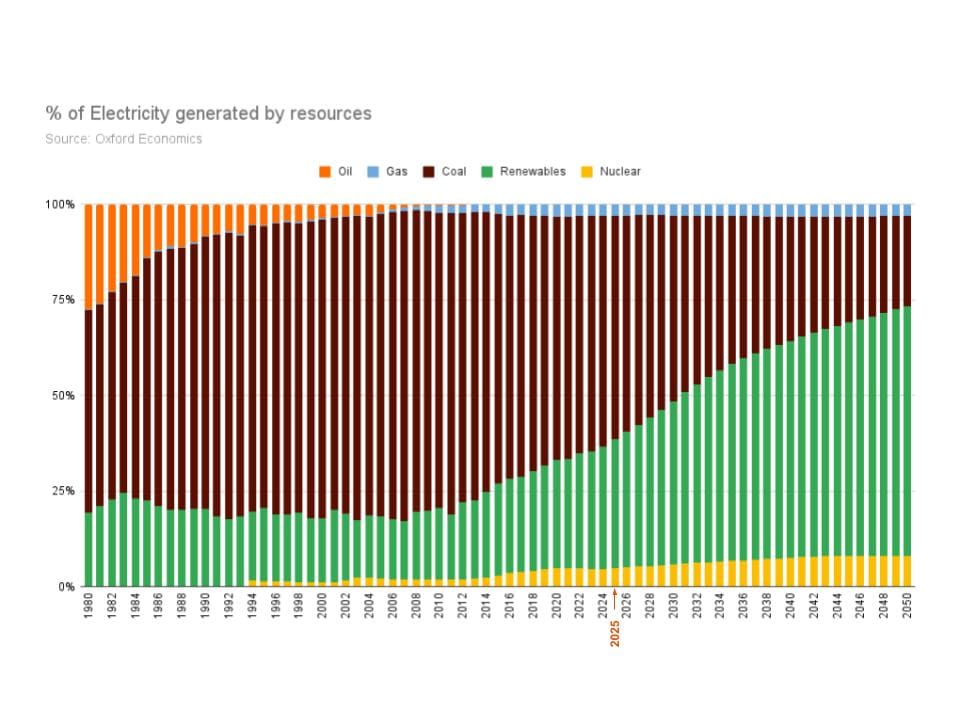

But the Chinese move on climate became very clear from 2020, when China — the world’s largest emitter of CO₂ in absolute terms also being the largest country by electricity demand — initiated a major shift in its energy mix, aiming to reach a peak in carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve neutrality by 2060.

While coal still accounts for nearly 50% of its energy production today, China has massively invested in LNG to offset coal and oil as a start, growing from one terminal in 2006 to more than 30 today. LNG is mainly supplied from Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Qatar, promoting long-term contracts.

On the nuclear side, China now has 58 reactors in operation and 29 under construction, soon totalling over 85 GW of installed capacity. France, by comparison, has an installed capacity of 63 GW.

The country has invested 890 billions of $ in renewable energy (solar, wind and hydroelectricity), deploying a total of 297GW in 2023 and 357GW in 2024 – ten times more than in the US, according to the “Lettre Hors Les Murs” du France-China Committee.

2024 broke a new record for wind capacity additions, with 79.8 GW installed. By the end of 2024, China’s combined solar and wind capacity reached 1,400 gigawatts (GW), well ahead of its 2030 target (1200GW).

China generated 38% of its electricity from low-carbon sources in 2024, just below the global average of 41%. It was the largest country by electricity demand. Hydropower remains China’s largest source of clean electricity, contributing 13% in 2024, as per Amber, a think-tank specialized in Energy.

More than one thousand sustainable energy power plants are on the pipe totalling another one $trillion investment in the country alone, says Globaldata.

The country has also secured the entire energy supply chain from upstream to downstream. Beijing owns 60 to 90% of the critical metals used in sustainable technologies, driving the competitive landscape at the global level. The country accounts for 80% of global production in solar equipment, ready to deploy outside the Mainland. The same trend is observed in the battery sector. This quasi-monopolistic situation and capacity stockpiling are being addressed by all other economies which, just like China, have a country to manage. As much as China advocates for the WTO framework, more than twenty years of intensive subsidies and the difficult opening of its own business and financial markets do not argue in favour of a trustful engagement.

But all in all, while the world really met China’s solist worrying abilities during the first salvo of tariffs, the second salvo at the beginning of this year saw China, South Korea and Japan agreeing to strengthen trade ties in response to US tariffs while working all around, with the European Union included, to find a common answer to the too-long-lasting lack of visibility and predictability of the economy. Multilateral and bilateral consultations are on their way to find this common ground.

KPIs and Uncertainties

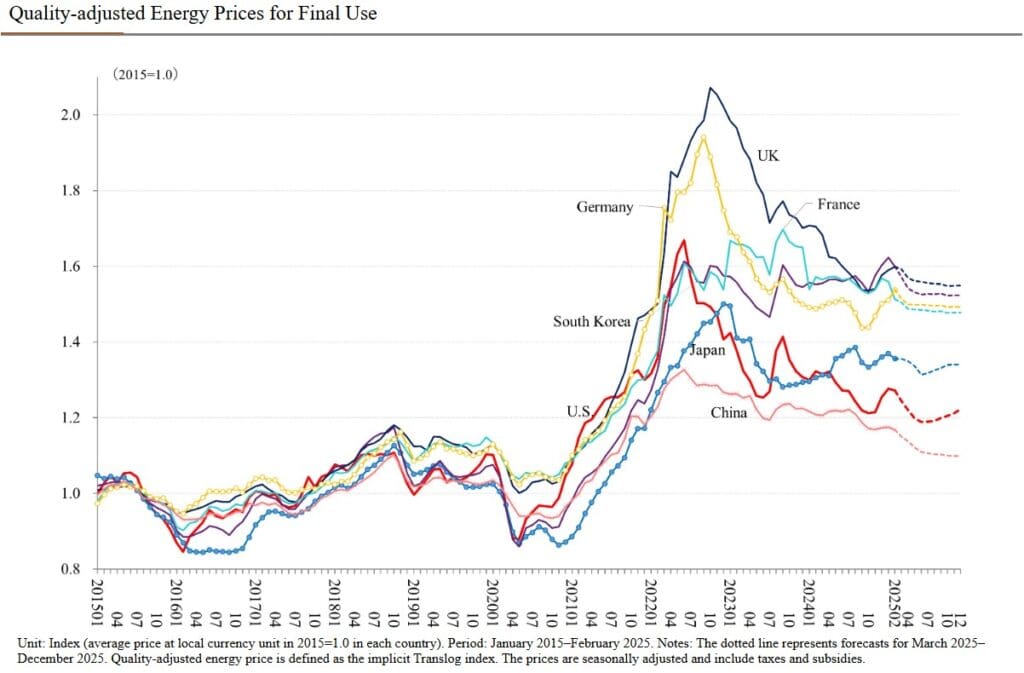

On one hand, electricity prices are still affordable. The upgrade of the industry is on the pipe that could improve business as well as prices. China’s trade surplus for March alone exceeded $100 billion, and is approaching $1.1 trillion in the rolling year. As per Globaldata, there is 2 trillion $ investments in 2025 and 26 in the energy, industrial and infrastructure sector, in China alone, not mentioning abroad business.

On the other hand, domestic demand is still very low despite consumer stimulus programs. Manufacturers are fighting to keep their market share in a tense market cycle, as analysed by Sophie Wieviorka, economist, specialist of Asia. The aftermath is that prices have been going down since the beginning of the year. Due to the tariffs, unless resolved in the meantime, exports are expected to fall in the coming quarters.

© Nomura Lab at Keio Economic Observatory (KEO), Keio University, Tokyo.

To conclude, China — supported by its international portfolio of diverse partners, advanced technologies, competitive sectors, economic stimulus measures, favourable energy prices and low inflation — is well positioned to remain a key contributor to global growth, despite not being the most ethical one yet.

We, at Aperam, look at the world as it is and act, every day, to be part of the concrete solutions that shape it.

Sources:

- https://www.comitefrancechine.com/les-lettres-chine-hors-les-murs/

- https://etudes-economiques.credit-agricole.com/previewPDF/181688

- https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/powering-chinas-new-era-of-green-electrification/

- https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/energy-transition/043025-china-has-established-125000-mtyear-of-green-hydrogen-production-capacity-nea

- https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep/rcep-overview#:~:text=The%2015%20countries%20within%20RCEP,or%2030%25%20of%20global%20GDP

- https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-industrial-power-rates-category-electricity-usage-region-classification/

- https://climateenergyfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/MONTHLY-CHINA-ENERGY-UPDATE-Feb-2025.pdf

- https://www.ruec.world/ECM_pE.html

-5,08%

-5,08%