Energy Sector Facing Unprecedented Headwinds

Home Energy Sector Facing Unprecedented Headwinds

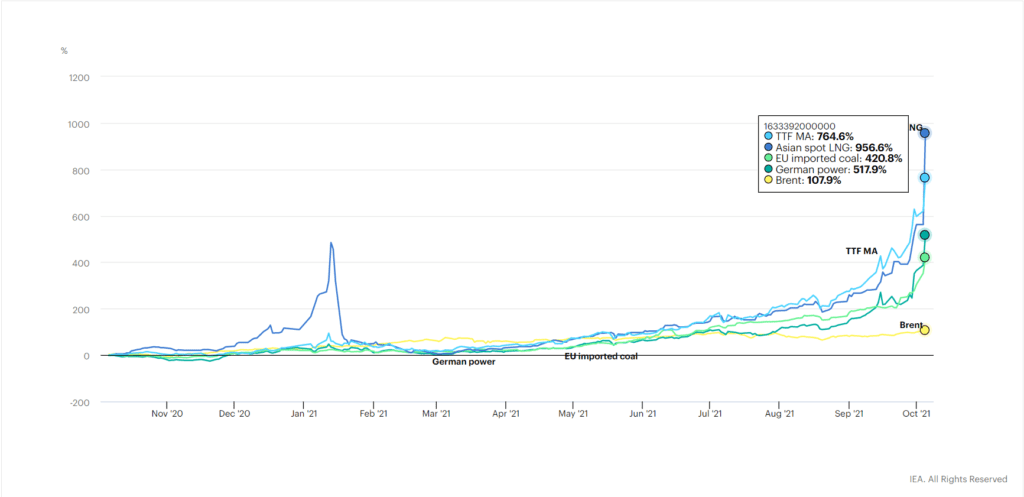

The price of energy is skyrocketing. As of October 2021, prices are at levels that haven’t been seen in decades: +764.6% for Dutch gas, +956.6% for spot Asian LNG, +420.8% for imported coal in the EU, +517.9% for German power, and Brent is soaring at +107.9% (as reported by the IEA).

Several factors explain these rises. To account for the Energy Shift and related demand, more and more O&G energy players are diverting funding towards climate related portfolios. But this is just one of the factors behind today’s unprecedented increases in energy prices. Past market behavior, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and climate aftermath have impacted production and supply chains and are thus the main drivers of today’s energy’s inflation.

Deficits of All Kinds

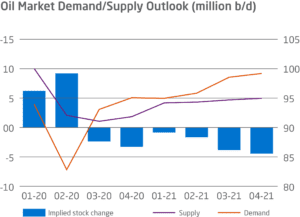

Let’s start by looking at market behavior. Since 2015, global investments in the O&G sector have fallen far short of 600 billion to a trillion USD of upstream needs, reaching a low point in 2020 (the result of the severe drop of energy prices in recent years). The 25% drop in demand and supply during COVID’s first wave did not help. This lack of investments has a direct impact on production. For example, according to IEA estimates, U.S. crude oil production in 2021 could be down to about 200,000 barrels per day. O&G companies have been indeed practicing capital discipline following the drop in fossil-based energy prices.

Further exacerbating the energy crisis are a number of weather related disasters that have caused supplies to plummet and stocks to dry up, therefore increasing prices. To illustrate, consider the below examples, which have been collected by NovEthic, a French CDC subsidiary:

- In South America, the Parana River, the third largest hydrographic network in the world, is drying up – losing an average of six meters in two months due to the lack of rain and deforestation. However, the Parana hydraulic power stations provide 55% of the continent’s electricity supply. To make up for this loss of supply, Brazil, for example, which is extremely dependent on hydropower, has turned to American gas.

- The U.S. experienced a decline in O&G production following Hurricane Ida during the summer of 2021, which forced the shutdown of 288 production rigs and resulted in a loss of 30 million barrels.

- In China, torrential rains caused the closure of some 60 coal mines in the Shanxi region, which provides 30% of the country’s 60% coal-based supply. This happened right at the beginning of the winter season.

- A similar scenario was seen in India, where heavy monsoon rains complicated coal mining and disrupted transportation networks.

- In September, the UK, home to nearly 11,000 wind turbines, faced significant wind shortages. In fact, wind energy accounted for only 7% of all electricity produced during this period, far short of its 24% average. To make up for this shortcoming, the country reopened a coal-fired power station.

- In France, the Chooz nuclear power plant, located in the Ardennes, was completely shut down in August 2020, the result of insufficient flow from the Meuse River, whose water is used to cool the system. Similarly, in 2019, the EDF announced a reduction in the power production happening at the Bugey plant (Ain), also due to insufficient water flows.

As if this was not enough, between January and September 2021, global LNG facilities have faced an abnormal amount of unplanned outages (+27% vs. 2015-2020 averages), leading to a drying up of stocks.

To make matters worse, storage levels were already low due to strong post-COVID double-digit growth in demand in 2021 and tighter-than-expected supply during and after the pandemic’s early waves. In Europe, gas storage levels dropped by 15%, well below their five-year average levels (per IEA analysis).

And let’s not forget that the overall energy market is also being impacted by supply chain issues, including shortages in the freight sector. This is causing difficulties with short-term delivery, further cutting energy supplies and boosting industrial worries.

Note: Assumes OPEC + fully complies with cut targets through 2021. Venezuela, Iran and Libya assumed to remain at October output level of 2.74 million b/d. Source: IEA, S&P Global Platts

In the meantime, Demand is soaring

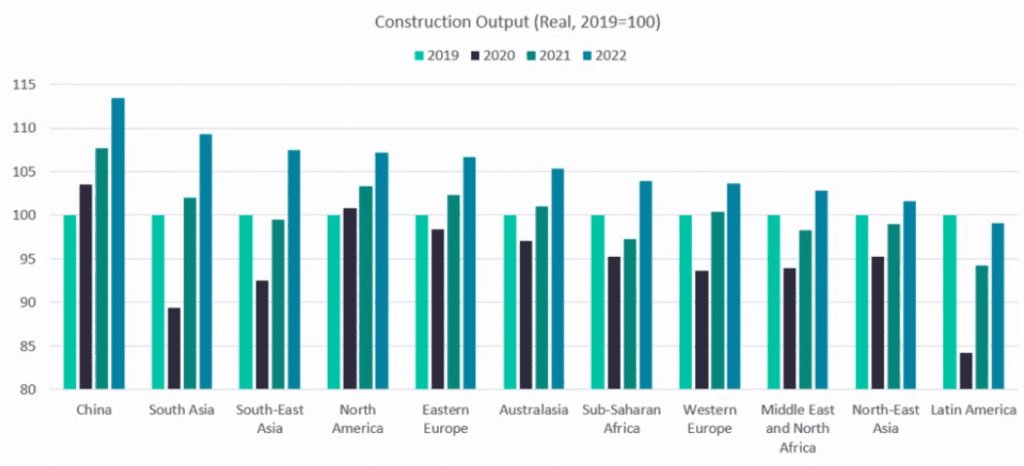

As most of the world slowly returns to ‘business-as-usual’ following a COVID recovery, economic growth is soaring everywhere, leading the IMF to predict a 5% growth in global GDP in 2022, under the actual baseline scenario.

Furthermore, much of this growth is taking on a new sustainability mindset. These include new infrastructure and technological initiatives, a focus on re-localisation, and greenfield industrial sectors being built in the mobility, energy, water, waste and sewage sectors – to name only a few examples of the sustainable growth that is currently happening. The infrastructural and the energy reset are indeed energy ravenous. Infrastructure spending vows are gaining momentum, nearing an expected US$2500 billion in investment worldwide, and almost US$2000 billion in energy and utilities alone, in 2022 (per Globaldata).

In that path, Russia expects to see a significant increase in gas demand from the Asia-Pacific region, particularly from China (+17%) and South Korea (+18%), up from the traditional 7-8% rate of growth. In the Union only, the demand of electricity to cope with the Green Deal H2 target by 2030, could increase by almost one-fifth (per Transport & Environment analysis).

Source: Global Data

What Solutions are at stake?

This decrease in production and supply is happening just as global demand for fuel is surging – a surge that will only increase as we move into the winter season. To solve the supply issue and curve pricing, several actions are being considered at the global level – all of which are in a constant state of flux.

The OPEC+, one of the price makers, agreed in November, to raise oil output by 400,000 barrels per day starting in December. The US was asking for a greater effort but, according to an OPEC panel of researchers, the OPEC+ output plan “would balance supply and demand needs at some point next year (2022), potentially before spring”. The next meetings will tell us more.

In the meantime, the US, China, India, Japan, and South Korea are already noticeably coordinating plans to release strategic reserves in order to reduce prices for consumers. This, however, has prompted criticism and retaliation from the OPEC+ group. The US alone announced the release of 50 millions barrels equivalent to less than three days of consumption in the United States though.

Norway, on its side, announced that its O&G sector will be « developed, not dismantled », a reversal in course from a few months ago when it said that the sector was almost closing its doors.

Other resources, currently on hold (and thus contributing to the deficit), such as the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, are waiting to be activated. Geopolitical concerns are indeed a factor.

All in all, the discussed governmental policies were set to face the actual O&G deficit in order to avoid a major energy-led crisis in the near term. Although the end of winter will ease supply stress, strong global demand is set to boost energy supply as seen. The use of actual fossil-based capacities and the numerous investments in renewables should match the demand and amplify the energy mix output, which will be key to effectively curbing global CO2 emissions and finding a lasting energy price equilibrium.

11,66%

11,66%